|

Book Chapter XXXII

Our early American ancestors were very sure of descent from more remote Scotch ancestors who were entitled, under the laws of Scotland, to a coat of arms. These American progenitors used, as rightly they could, the "achievement" of their fathers by an imprint upon stationery, carriage doors, tableware, etc. Washington and other great Americans made a similar use of their respective family arms. Some of those old imprints which our early American fathers used are yet extant. There are a greater number of later reproductions. Many of these have suffered sadly at the hands of artists not well versed in Scotch heraldry; but even in most of the unscientific emblazonments enough of the main features have been retained that we may trace the descent of the reproduction, so to speak, through the founders of our American families, back to the earliest known Ewing arms. The result of these comparisons is most important to our genealogy; and this result, coupled with the tradition, in all our branches, that a remote Scotch ancestor once bore these arms, is very satisfactory evidence of our descent from that ancestor. In this day and time, to assist in determining pedigree, these heraldric devices of our ancestors are of the greatest importance. In fact, since the warrior laid aside his armour, the chief function of armorial bearings, or coats of arms, or ensigns armorial (as synonymously expressed) has been to "distinguish families." (Sir George McKenzie, Science of Heraldry; Stevenson, Heraldry in Scotland; Woodward's Heraldry.) Nisbet is authority for the statement that coats of arms "are the most certain proofs and evidences of nobility." For these reasons each family of this day should as carefully keep the arms certainly known to have been the property of a remote ancestor, as it does a family record in the family Bible. Eugene Zieber, in his Heraldry in America (1855, p. 33), says there "is surely no reason why any individual in America should be deterred by ignorant or malicious criticism from preserving, for himself or his children, the heraldric devices which were borne by his ancestors, even though in his own land such devices have no governmental recognition." "Heraldry is usually a safe and reliable guide in case of pedigree and inquiries into family history," correctly remarks McEwen, the late Scotch author of Clan Ewen. Nisbet, an early Scotch authority upon arms, in the preface of System of Heraldry, 1816 edition, also says: The original design of heraldry is not merely show and pageantry, as some are apt to imagine, but to distinguish persons and families, to represent the heroic achievements of our ancestors, and to perpetuate their memory; to trace the origin of ancient and noble families, and the various steps by which they arrived at greatness; to distinguish the many different branches descended from the same families and to show the several relations which one family stands in to another. Hence, remember that heraldry, in this case called in to trace our descent, is recognized by authorities as "usually a safe and reliable guide in cases of pedigrees and inquiries into family histories," we shall go back to find what the earlier Scotch records disclose as to Ewing arms, and determine the bearing of that evidence upon the extant reproductions of the arms which our ancestors handed down to us as emblazonments of their ancestral arms. A preliminary glance at the origin of the use of the coat of arms in Scotland will assist us. What, in a heraldric sense, is a coat of arms? Heraldry is the science that treats of blazoning or describing in proper terms armorial bearings. "Heraldry, according to various principal theories, arose from the necessity of having distinguishing devices on seals, or on armour in the tournament, or in war. It is true that these first necessities no longer exist, but a time-honored instance does not become an anachronism by merely surviving the circumstances which first called it into being. In the days of chivalry the display of heraldric cognizances was not confined to their owner's seal, and the armour in which he tilted, or the banner under which he and his followers went to war. While these, their first uses, were still being served, heraldric ensigns became genealogical as well as personal. They were not only displayed on the knight's surcoat, but they might have been seen (and generally were) on his lady's mantle and his daughter's kirtle; they were emblazoned in his glass windows, and carved in stone both on his castle and on his church, and so on," so J. H. Stevenson, Heraldry in Scotland (Glasgow, 1914), tells us. Hence, as correctly defined by a recent authority, "Heraldry is the science which teaches us how to blazon or describe in proper terms armorial bearings and their accessories," as F. J. Grant, Rothesay Herald, The Manual of Heraldry (Edinburgh, 1914), gives the rule. Sir George McKenzie, accepted by Stevenson, advocate unicorn pursuivant of the Scotch King Herald's office (Heraldry in Scotland, 12), says: "Armorial bearings are 'Marks of hereditary honor,' given or authorized by some supreme power to gratify the bearer or distinguish families." From the earliest dawn of history men used ensigns, banners, standards and badges as distinguishing emblems in war and in other affairs. Then came seals, devices circular or in other form within which were represented wheels, birds or other objects. Seals were used in the early days by persons, such as kings and other potentates, who could not write. In time seals came to be generally used as evidence of authenticity. From that practice in England we get the custom in this country, now abolished by statute in some States of the United States, of writing the word "seal" within a scroll after the signature to deeds and other important documents. This seal may be regarded as the earliest form of device which developed into designs, usually in colors or "metals," now known as coats of arms. In ancient and medieval times men, trusted and stalwart, carried messages from commanders in times of war and from sovereigns in both war and peace. Such messengers came to be known as heralds. It was part of their function to challenge to battle, proclaim war or peace, and to denounce or proscribe as commanded by king or other functionary in authority. The better to attest his authority the king's herald bore a reproduction of the king's seal upon the outer coat, as did the assistants who were called pursuivants. Ancient and medieval warriors wore armour, we know. Armour continued in general use until about 1300. (Bulfinch, Age of Chivalry, pt. 2, p. 22). The head was encased in the helmet and so the identity of the armored warrior was difficult or impossible. This led, it is believed, to the emblazonment of some distinctive device upon the outer or surcoat, thus giving rise to the term coat of arms. Thus armorial devices became important; and a person's armorial bearings, that is the distinctive design which he bore, came to be a badge of honor as well as a mark of identity. The figures or representations of which the coat of arms is composed came early to have a meaning as well as being an identification. For instance, Alexander II of Scotland, who ruled 1214 to 1249, "was the first Scotch king to use the lion rampant on his seal." (McMillan, Scotch Symbols, 50). When later the coat of arms came into use in Scotland the lion rampant became and yet is the chief figure on the arms of the king of the Scots, now quartered with the arms of England and Ireland, since the king of Great Britain is now king of Scots. Hence, the lion rampant is significant, as an early meaning, of royalty or royal descent. Hence we see that early it became important to protect both heralds and armored warriors against improper impersonations, and all the more so as nobles and gentlemen of distinction came more and more to use symbols and seals to indicate their authority or rank. Too, the herald came to be regarded as the custodian and protector of the seal or arms of his chief, the king or other person of authority as might be. So heralds became conspicuous figures at great functions, particularly the coronation of kings, bearing upon the coat or upon a banner the king's arms and taking part in the exercises. It is said that heralds at arms, for the first time at such functions, attended the coronation of Robert II of Scotland in 1371; and it is certain that soon thereafter the authorities of Scotland created what is known as the office of the Lyon King of Arms, the chief officer of which is the Lyon King of Arms, or Lyon Herald. This officer now has three pursuivants or herald assistants. The date at which armorial bearings became extensively used or even appeared at all is uncertain; but in all probability coats of arms became generally recognized as important property rights and widely used for one purpose of another toward the end of the twelfth century, says McMillan, a recent learned Scotch writer (Scottish Symbols, 302). Stevenson (Heraldry in Scotland) and other authorities concur in this view. That gives us the approximate date as between 1175 and 1200, as the time from which we may begin to think of coats of arms somewhat as understood in later days. Of course from that to earlier times such emblems fade back through the wearing of mailed armour to the earliest insignia adopted to distinguish the man or the unit in battle or in important civil function. McMillan says that it is not certainly known when the dignity of Lyon King or Herald of arms was first conferred, as such an officer existed before the statue creating his office. From an early day the Lyon has been installed with elaborate ceremonies; and he early came to be the judge which passed upon disputed claims to arms and decided many other matters in connection with the use of arms. "The king alone can give a grant of arms, and this he does in Scotland through the 'Court of Lord Lyon,' at the head of which is the Lord Lyon who holds directly from the crown . . . In Scotland the improper assumption of arms, was made a statutory offence by act of Parliament passed in 1592;" and "the penalty is fine or imprisonment. ... British subjects residing in British colonies apply for grants of arms to the authority of the land from which they are sprung. A descendant of a British subject who is a citizen of another country cannot get a new grant of arms in Scotland, but he may matriculate the arms of an ancestor in the same way as if he were still a British citizen," McMillan explains in Scottish Symbols (1916), 303, 307. But the Lyon Herald of Scotland has lost much of his ancient function, which is now in the Herald's College of Great Britain. The Herald's College of Arms, instituted in 1484, is of England rather than Scotland. It once had authority to inquire into and to enforce regulations pertaining to heraldric devices; but in later years the College has no compulsory power. The Herald's College and those in England who have some supervision over arms "at present take no note whatever of the emblems or devices" of Scotland or Ireland: "while undue prominence is given to those of England," remarks McMillan. In 1592 a law authorized the Lyon King of arms and his heralds to hold "visitations" throughout Scotland "to distinguish the arms of the noblemen and 'thairafter to matriculate thame in thair buikis and registeris'." But, unfortunately, if the Lyon got a record of the arms claimed at the time it was imperfect and not now in existence. In 1672 all bearers of arms were required to register them in the Lyon's office. But, evidently, even that law failed to bring about a record of many old arms belonging to prominent families before its enactment, and of many such no record to this day exists. So it is that the earliest records of arms belonging to Scotch families are found in "armorials" gathered by private collectors or painted by herald painters,—for the colorings are of vast importance. Of course no private work contains all of the arms of its day. One of the earliest of such private records which have come down to a modern day was made by Matthews Paris, who was born in 1200 and who died in 1259. The armorial which he left is now in the British Museum. (McMillan, Scottish Symbols, 51). What is known as Gelre's Herault d'Arms, "which forms a general armory of Christendom at the period," comments Stodart, has "1334 placed before several shields, and in one place 1369 is written." Grant says this work was "executed about the year 1370." Before the German invasion of Belgium it was in the Royal Library at Brussels. In it are reproduced forty-five shields of Scotch arms, of which thirty have crests. Grant says it "gives the arms of the king and forty-one coats of Scottish nobles." Stodart of the Lyon's office published the Scotch part of this work in 1881. Then comes the splendid Armorial de Berry of the Bibliotheque National of France (The National Library of France). The compiler was appointed herald by the French king in 1420; and thereafter traveled far and near and painted arms for his collection. Of course he did not get all, tho he painted 122 Scottish coats; and I do not know how he determined which he would copy. As communications were slow and difficult in those days, no doubt each of these painters never heard of many coats of arms. Apparently the earliest official record of the Scotch Lyon's office was made in 1542 according to Sir James Balfour Paul, Lord Lyon King of Arms, Edinburgh, 1903, in An Ordinary of Arms. The register of that date was made by Lindsay, Lyon King of Arms, and is the earliest official register of Scottish arms, says Grant. But it is sadly wanting in completeness so far as existing arms which belonged to many prominent families. As Nesbit says: "Many of our most ancient and considerable families have neglected to register their arms notwithstanding the act of Parliament . . ." The next record we shall notice, and one most interesting to us, is known as the Workman or Forman Manuscript, because once owned by James Workman, a herald painter. It is entitled Illuminated Heraldia; that is, the arms contained therein are shown in colors. It was made in 1565-66, and some authorities say parts of it were as early as 1508 and 1530 (Stevenson, Heraldry in Scotland, 114.) A facsimile reproduction of the arms of the Workman Manuscript was published by R. R. Stodart, of Lyon's office in Scottish Arms, Edinburgh, 1881. This Workman Manuscript shows the Ewing arms, and is the earliest information regarding these arms under any spelling of our name, as far as I have been able to discover. (See page 66 of Stodart's volume one and page 215 of vol. two.) I give a print from a photographic reproduction of Stodart's facsimile of Workman. To a casual eye the first letter of the name might be taken for a capital I; but without exception the Scotch and other authorities read it E. I am inclined to believe that at that time it was not infrequent that the small letters were made large in size to represent capitals. Too, the name as evidently written in the Workman Manuscript, is an interesting sample of writing nearly 400 years old. On the same page of Stodart are the Barriman arms, the first letter of the name being a small b. That was a day, we must remember, before either capitalization or spelling was uniform or governed by modern rules; and, at any rate, the name was written, so far as we know, by the painter. But the spelling is further evidence that even at that early day Ewing was the better form of the name. The next specific Scotch record we have, giving the emblazonment of the Ewing arms, is a reproduction by Nisbet, published in 1722, the arms being at that date borne by John Ewing, of Craigtoun, who inherited from his ancestors, but how far back Nisbet does not say. I give photographic reproduction from Nisbet's work.

The ornamentation outside of the shield is common to a large number of arms shown by Nisbet, and constitutes no distinctive part of the arms. The shield and the figures (charges) therein, as shown in the Workman Manuscript, are the most important part of the emblazonment and the distinctive part of arms. The shield is the one necessary part of the achievement, and may comprise the whole of a coat of arms. "The shape of the shield is not essential to the owner's heraldry;" but the type is important. The "type of shields most in use has varied at different times." (Stevenson, Heraldry in Scotland, 134.) Bearing these facts in mind, we cannot doubt that the Craigtoun Ewing arms are founded upon those shown by Workman in 1565; and it is reasonably certain that the Craigtoun (or Craigtown) arms mark family succession. The type of the shield is one item of the evidence leading to this conclusion. That type belongs to a period of about 300 years ending earlier than 1499. A Ewing tombstone dated 1600, in Bonhill Churchyard, has upon it these arms; and McEwen supposes that this stone marks the grave of one of the Ewings of the Craigtoun family. Ross tells us that Bishop Ewing found upon a Ewing gravestone in the old Ewing burying ground on the banks of Loch Lomond, in the midst of our old clan lands, believed to be the stone of the grave of the bishop's grandfather's cousin, "the family coat of arms." (Ross, Memoir of Alexander Ewing, 101.) There are six entries of Ewing arms, each slightly differentiated from the others to denote succession, in the Lyon's office of Scotland, made since the old records which I have described, and all of them are founded upon the earlier arms. The editor of "Clan Ewen" says: "All the Ewing arms are founded upon those of Ewen or Ewing of Craigtoun. He belonged to the family of Keppoch in Dumbartonshire." (Clan Ewen, p. 45.) Spooner, the American genealogist, says: "The arms of the Ewing family show several variations, but there is a substantial uniformity in those borne by the Scottish branches." This uniformity means common origin; and, taken in connection with our traditions, establishes the fact of family descent from the family to which the arms earliest belonged. "All members of the same family carry the same bearings in their coat of arms," and to distinguish the principal bearer from his descendants or relatives recognized signs are used. "These signs are called differences." This differencing or cadency is usually shown "by bordure, which is again further differenced among the younger sons of younger sons by being engrailed, invected, indented, embattled, and so forth." The oldest son inherits, in Scotland, the right to the "undifferenced" arms of his ancestor; but younger sons can "matriculate" the family arms. It appears that the Ewing arms registered in the Lyon office were entered by younger sons. "Sisters have no difference in their coat of arms. They are permitted to bear the arms of their father, as the eldest son does after his father's decease." Now compare the arms of the American branches of our families, representative reproductions of which are shown herein; and the arms of Ewing of Craigtoun, and those shown upon the Bonhill tomb, and those shown upon the tomb of the family to which Bishop Ewing belonged and then compare these with the Workman reproduction—and then it is seen that it does not require an expert to see the identity. Distorted and abused as are some of the late emblazonments, their source in the Workman arms of 1565 is yet apparent. Entitled to preserve the heraldric devices of our ancestors, believing that our early American fathers would not claim what under the Scotch law was forbidden, we are warranted in accepting the identity of the American with the Scotch source, those devices with the oldest Scotch arms, as establishing, prior to 1565, the common ancestor of our American branches. The late R. S. T. MacEwen, of Scotland, in his "History of the Clan Ewen," from which Highland clan he erroneously gets the Ewings (though probably correctly the MacEwens), as shown in another chapter, says that "the arms, themselves, throw no light on the family history of the Ewens or Ewings." He was under the impression that the Ewings arms, a cut of which he gives, and which are taken from Nisbet, "came into the Ewen or Ewing family with the lands of Craigtoun by the marriage of Walter Ewen, or Ewing, writer to the signet, with the eldest daughter of Bryson." He says further: "These arms belonged originally to Bryson of Craigtoun;" and that so coming into the Ewing family they "appear on a tombstone of 1600 in Bonhill Churchyard," marking the grave of Ewing of Craigtoun. His authority, he says, is "Nisbet, System of Heraldry (1722)," "one of the best authorities on ancient Scottish heraldry." He adds further that in that work "it is said that these arms are carried by John Ewen, writer to the signet (that is, a lawyer in a certain Scotch court), and further on, with reference to Bryson of Craigtoun, that 'this family ended in two daughters; the eldest married Walter Ewing, writer to the signet; they were the father and mother of John Ewing, writer to the signet, who possesses the lands of Craigtoun which belonged to his grandfather by the mother's side, and by the father's side he is male representer of Ewing of Keppoch, his grandfather, in the Shire of Dumbarton; which lands of Keppoch were purchased by a younger son of the family, who had only one daughter, married to John Whitehill; whose son Thomas possesses the lands of Keppoch, and is obliged to take upon him the name of Ewing.'"

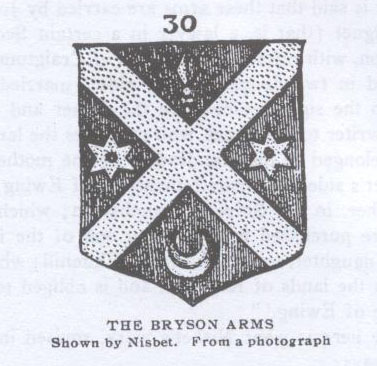

Photo-reproduction of arms recognized by Dr. John Ewing of the University of Pennsylvania, as belonging to his Scotch ancestors. The Ewing arms are on the reader's left,—sun, chevron, banner, &c. The figures on the right are those of other arms. Both originals of this and number two were used very early in America, and when the first American ancestors of our family were yet living. Now here is what Nisbet's work, revised in the 1804, 1816 edition, says: In our New Register Mr. Andrew Bryson of Craigton carried gules, a saltier between two spur-rowels in fesse, a spearhead in chief, and a crescent in base or. Plate 11, fig.30. This family ended in two daughters; the eldest of them was married to Walter Ewing, Writer to the Signet, father and mother of John Ewing, Writer to the Signet, who possesses the lands of Craigton, which belonged to the grandfather by the mother's side; and, by the father's side, he is the male representer of Ewing of Keppoch, his grandfather, in the shire of Dumbarton; which lands of Keppoch were purchased by a younger son of the family, who had only one daughter, married to John Whitehill, whose son Thomas possesses the lands of Keppoch, and is obliged to take upon him the name of Ewing. The arms of Ewing are carried by John Ewing of Craigton, Writer to the Signet, of which before, page 412. (Ib. p. 428.) That is quite a different story! I don't see how MacEwen, a barrister-at-law, practicing in one of Scotland's courts, made so great a blunder. Nisbet does not say that John Ewing carried the Bryson arms. Read his description of the Bryson arms, look at the photo-reproduction as Nisbet gives them in "Plate 11, Fig. 30," reproduced herewith, and it will readily be seen that the Bryson arms are not the Ewing arms. Not this only, Nisbet says plainly: The arms of Ewing are carried by John Ewing of Craigton, Writer to the Signet, of which before, page 412.

Turning back to page 412 we read: "Workman, in his Illuminated Book of Arms, gives such a chevron (that is, a chevron embattled, see the illustration where the chevron looks like a stairway) to the name EUENE, argent, a cheveron pignone azure, (for which our heralds say embattled) and ensigned on the top with a banner gules, between two stars in chief, and a soleil of the last in the base, and the same are carried by John Ewen, Writer to the Signet, as in Plate of Achievements." That is every word I find upon the subject in Nisbet, whose monumental work was prosecuted largely by funds supplied by the Parliament of Scotland. So that Nisbet identifies the arms of John Ewing in 1722 with the arms shown in the Workman Manuscript of 1565. The spelling Euene is, as I understand it, an adjective of Ewing, used to indicate the clan or family. On the other page of his book Nisbet spells the name E-w-i-n-g each time, and on page 412 he spells John Ewing as John Ewen, showing, as is true, that in 1722 spelling was not yet uniform, but that the form Ewing was the more general. Ross, in his Memoir of Bishop Ewing, a much later work, says Bishop Ewing belonged to "that branch of Ewene stock" which was early numerous along Loch Lomond in Dumbartonshire,—and this is the stock claimed rightly, I am sure, by our ancestors. Further, Nisbet says he reproduces the arms "belonging to the name of Ewing as in the Plate of Achievements." Among the many he reproduces we find those arms on Plate 21, which we have reproduced from a photograph. A glance identifies those arms with those of the Ewing clan of 1565. Also these reproductions show unquestionably that the Ewing arms and the Bryson arms are not the same. Nisbet gave the arms, it will also be noticed, as embellished in 1722, with the crest and motto. Most of the arms shown by Nisbet have the ornamentation outside the shield, and that elaboration has no distinctive value." It is merely a later cumbersome "embellishment." This photograph of the Workman arms is from Stodart's reproduction of Workman. Stodart, at the time he reproduced his work, was Lyon King of Arms of Scotland; and he gave us the most correct representations of the most authentic and genuine coats of arms known to his office. Hence the arms we now claim as evidence of pedigree evidently come from the same source as those of the Keppoch branch of our clan. Nisbet says that John Ewing, whose father married Bryson's daughter, "is the male representer of Ewing of Keppoch, his grandfather, in the Shire of Dumbarton." Being the male representer he was entitled to the undifferenced arms of his ancestors. But apparently we did not descend from the Ewing-Bryson branch. We may have descended from a younger son of the Keppoch family, but probably go further back. As the younger son was entitled to "matriculate" the arms of the father, our arms probably come down through the younger branch, a generation of more older than the Ewing-Bryson branch. However, Stodart says that Robert Ewing, the last of the male line of the Craigtoun family, was dead in 1781 "when his heirs were his sisters, Elizabeth, wife of Rev. John Bell, and Agnes, wife of Edward Inglis of Edinburgh." Finally, the estate and arms came into collateral Ewing hands or a descendant of one of the girls assumed the Ewing name; and in 1869 Alexander Ewing, merchant of Glasgow, registered these arms as described by Spooner and as given presently. Hence, the arms, or "achievement," on the tombstone of 1600 in Bonhill Churchyard," "supposed to be (the tomb of) Ewing of Craigtoun," of which McEwen speaks, are, it is clear, Ewing arms, and not the Bryson arms. Now, all the arms of the Scotch Ewings, there being six registrations in the Lyon's Office, all subsequent to the Workman Manuscript, and most of them comparatively recent, show a general uniformity with the old arms existing earlier than 1565. These were evidently the arms found upon the tomb of the Ewing buried upon the banks of Lomond upon which tomb Bishop Ewing saw "the family coat of arms," and to whose family the bishop belonged. They were carved upon the stone of the Ewing buried in Bonhill in 1600. The American Ewings of whom I write have handed down to us reproductions of their ancestors' arms, which reproductions yet exhibit the same uniformity and show that they are identical with the above-mentioned reproductions; all being the arms evidently existing before 1565. An ancient common ancestry of all the families thus distinguished is thus shown. Now, then, just a few words that we may better understand how our arms should be emblazoned. In ancient heraldry "the essential parts of arms are tinctures and figures." The tinctures are two metals (colors, we say in modern painting) and five colors. Old heralds speak of the gold and silver colors as metals. Originally the warrior's shield was of polished metal, either actually or resembling silver or gold, or, at least, in the case of a potentate, having gold embellishments. The Latin names for these metals are used and nearly always in descriptions abbreviated: gold, orgent, or; silver, argent, ar. The colors used of old are azure, blue; gules, red; sable, black; vert, green; purpune, purple;, and are generally abbreviated, az., gu., etc. Some of the modern productions of Ewing arms do not show the shield. For instance, see the picture of the Maskell Ewing, Jr., and the John Ewing reproductions. Either the shield was omitted by some unversed modern artist, or the figures are mounted in something of the nature of a lozenge to denote descent from a daughter of an ancestor who bore arms, and who, if such were true, evidently married a Ewing, thus handing down to that John and that Maskell the Ewing name and arms through two slightly differing sources, though almost certainly in such a case both parents some years earlier of the same family.

Photo-reproduction of the arms recognized by the Hon. Thos. Ewing family as coming from Scotch ancestors. The banner is flung out in the wrong direction, due possibly to the use of something resembling a lozenge. The bars in the helmets and the lines indicating colors in the originals from which both halftone reproductions were made show clearly. On the right-hand side of the John Ewing arms here shown are figures from the arms of some other family into which one of the parents or an ancestor of one had evidently at one time married. It is not unusual to display upon one shield or lozenge both paternal and maternal arms. In modern days ladies do not use a shield upon which to display the charges of arms—women are not supposed to fight. In place of the shield the lozenge is used. Grant defines a lozenge as "a diamond-shaped figure, but not rectangular, two of its angles being acute and two obtuse." Then he adds: "The arms of ladies are always displayed on a lozenge instead of an escutcheon." In the earlier days ladies of rank bore their arms upon shields, however. Our shield, or our lozenge, then, and its bearings, or figures, are thus described, as we saw, by Nisbet as given by Workman, and should be accordingly emblazoned, disregarding anything for difference, and accepting the arms as Workman found them as coming down to us through the oldest child from generation to generation. Argent, a cheverone pegnone azure (for which our heralds say embattled), and ensigned on the top with a banner gules, between two stars in chief, and a soleil (sun) of the last in the base. Since 1565 something has been added to the banner, and as thus modified the Ewing arms are: Argent, a chevron embattled azure, ensigned with a banner gules charged with a canton of the second, thereon a saltire of the first, all between two mullets in chief and the sun in his splendor in the base of the third. This describes the arms registered by Alexander Ewing, merchant, of Glasgow, in the Lyon's Office in 1869; and doubtless he registered the arms as inherited by him. It is very striking that, as far as I have seen, the canton and the saltire were displayed on emblazonments used by our American ancestors for at least one hundred and forty years before similar arms were thus registered by our distant kinsman, the merchant of Glasgow. The old arms which the Workman manuscript has show no saltier, a cross similar to the letter X. The saltier must have been added, therefore, to our banner since 1565. Some Scotch arms bear the saltier which is said to come down from an argent saltier on an azure field which adorned the banner of a confederacy between the Scots and the Picts which resulted in their killing the Saxon King Athelstan in East Lothian; but that was back in 941. Had that been the source of our saltier it certainly would be shown on the arms given by Workman. The saltier, which came to be known as the St. Andrew's cross, after 1557 when the Scotch barons entered into what is generally known as the first Covenant for the support of the Protestant religion, came to distinguish the banner of the Covenanters; and that, it appears most probable, is the origin of our saltier. In non-technical language, here is the description, and it indicates the way our American emblazonment of our ancestors' arms should be made: The shield is of silver; upon the shield is an azure-colored chevron embattled (that is, resembling a stairway, as shown in the illustration); on the point of the chevron is a red banner, flung out to the right; on the banner is a canton, that is, a quarter, the upper left quarter as one looks at the picture, of azure color of the second (meaning of the second color mentioned, as colors are not repeated, but given as first, second, third, etc.); thereon, that is, on the canton, quarter, a saltire, an X-shaped cross, of the first, that is, of silver; all between two mullets in chief, that is, between two stars in the upper half of the shield; and the sun in his splendor, that is, the full burst, in the base, of the third, that is, of red—the mullets, stars or spurrowels, and sun are of red, red being the third color given in the technical description. Upon the shield, as shown in the photograph from Nisbet, place the helmet and upon it the lion, holding in the right paw a mullet or star in red. In a print such as Nisbet gives colors and metals are indicated by the direction of the lines, by dots, etc. For instance, nothing upon the face of the shield indicates silver, to represent steel; the horizontal lines in the chevron indicate azure; the perpendicular lines in the stars and the banner and in the sun indicate red; and red is the color of the head and body, mostly, of the lion, the checkered lines of the right leg indicating a darker color, and so along the back, etc. The claws and tongue should be blue, though this is not indicated by the picture. The motto may be placed as shown by Nisbet or as indicated in the halftones from the arms of Dr. John Ewing and from those of Maskell Ewing. The dots, by the way, in the cross and stars of the Bryson arms indicate gold, it may be interesting to remember in this connection. In reproducing our arms there should be careful compliance with these requirements. For difference, that is to mark descendants of younger children, there should be used some figure within the shield, a bird, a leaf, or any appropriate thing; or an indented or other border. For instance, I have in my collection a painting of our arms having two birds in the upper chief, that is, the upper half of the shield; and many generations ago these were placed there for difference. But few of us in America now know whether our ancestor of the remote Scotch days was the oldest or youngest, and as arms to us now are of value mainly to indicate remote Scotch ancestry, a difference mark is not, unless it be known that it should be used, important in emblazoning for our use. Let's glance a moment at the "appendages" of our shield in concluding: Strictly speaking, armorial bearings are confined to the contents of the shield . . . Heralds have always regarded the appendages to the shield—supporters, helmet, motto, mantling, &c.—as being less important than the charges proper. These, however, add much to the interest of the coat-of-arms, and deserve more than merely a passing notice. The technical word for the entire composition is 'achievement.' The earliest known Scottish seal containing crest and supporters, as well as the arms proper, is that of Patrick, Ninth Earl of Dunbar, 1334. The reproduction herein from the Workman Manuscript shows Ewing arms "proper"—no supporters, no crest, no motto, no helmet, no mantling. The reproductions of the arms used by Maskell Ewing, Jr., by Thomas & Anna C. Ewing, and others show appendages, some of them very modern as to Ewing arms. Of course we know that the modern appendages are of no genealogical value to us and have no heraldric significance; and so we consider only such as were evidently used by our Scotch ancestors. "The helmet is a purely ornamental accessory of arms, and is placed directly above the shield. It varies in design according to the age to which it belongs, and in position and character according to the rank of its owner," says Matthews. As laid down by Grant, a Scotch herald: [The helmet is an] ancient piece of defensive armour; it covered the face, leaving an aperture in the front, secured by bars; this was called the visor. The helmet is now placed over a coat of arms, and by the metal from which it is made, the form, and position, denotes the rank of the person whose arms are emblazoned beneath it. The helmets of sovereigns are formed of burnished gold; knights, esquires and gentlemen, polished steel. All helmets were placed on profile till about the year 1600, when the present arrangement appears to have been introduced into armory. The position of the helmet is a mark of distinction. The direct front view of the grated helmet belongs to sovereign princes and has six bars. The grated helmet in profile is common to all degrees of peerage, with five bars. The helmet without bars, with the beaver open, standing directly fronting the spectator, denotes a baronet or knight. The closed helmet seen in profile is appropriated to esquires and gentlemen, … Now, since there "can be no doubt that the heraldric helmet was not originally a distinguishing ensign of rank" (Stevenson, Heraldry in Scotland, 201), the position of the helmet found on the modern reproductions of Ewing arms does not assist us in learning the rank of our earliest ancestors who bore arms at least prior to 1565. Of course as there were an hundred years between that time and the birth of our William Ewing, the father of Nathaniel of Cecil County, and his contemporary kindred in Scotland and Ireland, branches of the family from the clan prior to 1660 had time and opportunity to acquire rank—different rank, in fact. It may be that this fact accounts for the differences in the positions of bars shown on the family arms of several American branches; or these differences may be the blunders of artists not versed in heraldry. For instance, the arms shown in The Ewing Genealogy (Houston, Tex., 1919); by Hon. P. K. and M. E. Ewing, appear to show three bars only. I am inclined to the opinion that somewhere back before Judge Ewing and his accomplished wife obtained the copy from which was made the picture they used, an artist blundered. The Ewing of Craigtoun arms, given by Nisbet, show very certainly the four or five bars; and the John Ewing reproduction, and that of Maskell Ewing, Jr., which are the arms belonging also to my immediate branch, show certainly an open visor and four or five bars, depending on how the count is made. All the American reliable reproductions of our family helmet which I have seen, are in profile; and none of them shows a closed visor. Hence, the rank indicated is something above that of esquire and gentleman. That all American copies of our arms which show the helmet, as far as I have found (except a few inaccurate copies of the old extant copies, made in the last few years), have the helmet in profile, is important, and this fact suggests that we go back to the family arms before 1600. As we have seen, Grant says "all helmets were placed on profile till about the year 1600." This position of our helmet bears out the traditions that the Ewings who were in the historic siege of Londonderry, Ulster, Ireland, 1689, and their contemporaries and close kin whose children came direct from Scotland to America, were from a common family earlier than 1600,—and of course from the ancestor of that family who was of an earlier day. It is natural that the arms, when the achievement was faithfully executed, would show as they existed at the time of the dispersion of the Scotch family. On the helmet of Ewing arms as displayed by the American family, and by our ancestors certainly earlier than Nisbet's reproduction made in 1722, is the lion rampant. This lion is the crest. In Stevenson's Heraldry in Scotland (p. 179) we are told: Ancient documentary seals, which are our chief authority for the antiquities of coat armour, afford us valuable information regarding crests, helmets, mottoes and other exterior heraldric ornaments. The crest (crista), as is well known, was a figure affixed at an early age to the warrior helmet for the purpose of distinction in the confusion of battle; and there can be no doubt that, like devices on shields, was used long before the era of heraldry bearings. So that it is probable that our crest, the lion rampant, holding a mullet (star) in the dexter (right) paw, is the most ancient part now shown upon our arms. The lion has long been the cognizance of the king.

McMillan calls attention to the fact that John of Fordun (now known

as John Fordun) in his Scotichronican, written about 1385,

claims that about 330 years before Whose mighty shield, The earliest known seal bearing a lion is that of Philip, Duke of Flanders, which dates from about 1164, according to Scotch authority. The first Scottish king to use the lion rampant on his seal was Alexander (1214-1249). He used the lion only; no fleurs-de-lis and no tressure. McMillan thinks probably the lion was used on banners before it became the ensign of the king of the Scots. Anyway, it is certain that the Scots in the army of Charlemagne, about 800 A. D., carried the lion as their ensign. The royal banner of Scotland is the lion rampant of red surrounded by the royal tressure on a gold field. "When shown in full blazon, the claws, teeth and tongue of the Scottish lion are colored blue in accordance with the rule of heraldry that these parts of a beast of prey should be of a different tincture from the rest of the animal. "The royal crest of the Scottish kings," it is even more interesting to note since the lion is our crest, "from the date of its first appearance on the helmet of King Robert II, 1370-1, has been a lion. On his great seal it appears statant guardant, but in the Armorial de Gelre (c. 1386) it is a lion sejant, crowned and with a sword in its right paw." Ours is the rampant lion, holding a mullet (a star) in the dexter paw. How the lion came to be one of the appendages of the Ewing shield I have been unable to learn. I am inclined to believe it comes to us from that distant day when our clan ancestors bore the lion on the tribal banner in battle. It is not at all unreasonable that some of them served in the Scots unit of Charlemagne's army, 800 A. D. It may be that our ancestors were entitled to the use of the lion as an embellishment of the shield by reason of descent from King Ewin. However, the Ewings are not the only Scotch family using the lion on the coat of arms, or as an appendage, notwithstanding the lion is to the king of the Scots much in the nature of a trade-mark to the owner in America. Upon this point it will be worth the time to quote again from McMillan's interesting book. Quite a number of Scotch families bear the lion rampant, and as a charge (or figure within the escutcheon) in Scottish heraldry the lion swamps all other animals put together. The arms carried by these families are not, however, infringements of the royal arms, as the distinctive combination of the lion rampant, double tressure and fleurs-de-lis is not found there. Lord Rosebery has a samble lion rampant on a white field in the second and third quarter of his shield, while the ancient family of Wallace, which gave Scotland one of its most stalwart defenders, bore a silver lion rampant on red field. The Edgars of Wedderlie, descendants from the old Earls of Northumberland, bore sable a lion rampant argent. The Crichtons carry a blue lion on a white field, while the MacMillan's lion is sable on gold. Certain families claiming descent from Scottish kings carry the royal arms, sometimes with a baton sinister or a bordure gabony to denote that their descent though direct is illegitimate. Gabony, or compony, is a heraldric term meaning composed of two tinctures, generally metal color, in alternate squares in one row. There is, however, no gabony in any Ewing arms. The lion, therefore, is, it is not at all unlikely, another link indicating our descent from the clan which got its surname from King Ewin. I am not sure whether or not our arms at an early day had supporters. Nisbet shows none. Some embellishments, for instance, the sheep, Masonic emblems, &c., appearing in connection with our ancient family arms as used by some of our American families, appear to be meant for supporters. But they are merely embellishments of modern introduction and, though interesting and suggestive, have no heraldric value. Audaciter, boldly, the ancient motto used in connection with their coat of arms by our early ancestors, may have been originally the clan war cry. Its laconic nature is given by authorities versed in heraldry as a reason for this possibility. The evidence shows that our motto was used in connection with the shield at a very early day; and it is not at all impossible that the present word is the Latin of an earlier word of the old Brythonic tongue. The motto, as Stevenson explains, "consists, as everybody knows, of a word or sentence upon a ribbon or scroll." That author further says that the motto "has been rarely changed, either in England or Scotland, by families of ancient lineage, and has generally proved to be as hereditary in its character as the charges in the escutcheon." Our family is certainly very ancient; and so there is every reason to believe that our motto has come to us unchanged from far down the centuries. The ancient character of our motto is one reason why I am of opinion that our ancestors were Britons of the Cymric stock and not Gaels or Dalriadiac Scots; and, hence not of the Clan Ewen of Otter, to which the McEwens or McEwans belong. The motto of McEwan of County Stirling, as given by Barrister McEwen, is Pervicax recti; and that of McEwan of Glasgow is Reviresco. Neither of these, clearly, came from our ancestral motto. McEwen says this McEwan (or McEwen) motto, before it was registered by the Glasgow member of the family "had been common to the McEwans everywhere for a long time previous, and had been used as a badge on seals." That author also says that McEwens of Glasgow are related to the "same families which are joined by the McEwens of Otter." Hence, in the strong difference between the ancient mottos of these two ancient families we have important evidence of their distinct origins. The James Ewing branch of Wheeling, West Virginia, has the arms and motto as they came from Scotland to the other members of our family; but that James Ewing branch has, according to a drawing sent me by James W. Ewing, attorney, of Wheeling, another motto which is placed on a ribbon at the top of the shield and about the base of the crest. This motto reads: Hang your banner on the outward wall. I have been unable to learn the history of that motto. Evidently it is comparatively modern and has been acquired by the branch to which it belongs since that branch left the common family from which it and our branches came. I am inclined to guess that this additional motto has some relation to the family connection with the famous Londonderry siege of 1689. Another attempt to copy the old arms comes to me from St. Louis. The chevron, as there given, is not embattled, a great error; the colors and tinctures are incorrect, and the helmet has a frontal display, for which I can find no valid authority. This copy, however, has three birds, and these probably come from some old copy which they were rightly used by younger children for difference. However, upon the whole it is quite clear to me that all so-called "Ewing arms" which I have seen and which are claimed by different branches of our family are, when incorrectly blazoned, badly done copies of the genuine original and in so far as they correctly disclose the essentials of the early parental arms are valuable evidences of descent. It is hoped, though, that in the future artists will follow more accurately the requirements. of pagePage last updated 13 October 2008.

|